The former Bishop of Ely, the Rt Rev Stephen Conway, is among those facing criticism in a report into a man described as “arguably the most prolific serial abuser to be associated with the Church of England”. The independent review by Keith Makin into the Church of England’s handling of allegations of serious abuse by the late John Smyth says the responses were “wholly ineffective and amounted to a coverup”.

The Makin report details what Stephen Conway – bishop of Ely from 2010 to 2023 -knew of the abuse, contacts made by his diocesan safeguarding officer with Cambridgeshire police, and the prominence he gave or not to a victim who approached him for support.

“John Smyth was an appalling abuser of children and young men,” says the report.

“His abuse was prolific, brutal, and horrific. His victims were subjected to traumatic physical, sexual, psychological, and spiritual attacks. The impact of that abuse is impossible to overstate and has permanently marked the lives of his victims.”

Smyth, a Reader in the Church of England, died in South Africa in 2018 where he was also under investigation for abuse, but before leaving this country his abuse of young boys was widely known.

“John Smyth’s activities were identified in the 1980s,” says the report.

“Despite considerable efforts by individuals to bring to the attention of relevant authorities the scope and horror of Smyth’s conduct, including by victims and by some clergy, the steps taken by the Church of England and other organisations and individuals were ineffective and neither fully exposed nor prevented further abuse by him.”

Fast forward to 2013 and the involvement of Bishop Conway and the church authorities at Ely.

“The abuses committed by John Smyth began to be formally known to the Church of England in this period,” says the report.

“The Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser, Yvonne Quirk, was in contact with a victim at the end of July 2013, following several months of this victim being in contact with a church officer, who was also a victim.

“Several opportunities were missed during this period to establish a formal report of the abuse that had taken place in the UK to the police. The notification to authorities in South Africa, regarding John Smyth’s possible continuing abuse there, was not followed up to ensure action was taken to prevent further abuse.

“From July 2013, the Church of England knew, at the highest level, about the abuse that took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s.”

The report says: “The Archbishop of Canterbury’s personal chaplain (a priest) and the Bishop of Ely were all made aware of the abuse, and Justin Welby became aware of the abuse alleged against John Smyth in around August 2013 in his capacity as Archbishop of Canterbury.

“It is most likely that other staff members there will have been informed at the same time in August 2013.”

Malkin says: “There was a distinct lack of curiosity shown by these senior figures and a tendency towards minimisation of the matter, demonstrated by the absence of any further questioning and follow up, particularly regarding the Church reassuring itself that a known abuser was not still actively abusing (albeit in a different country, but this does not diminish the moral responsibility on people).

“The conclusion that must be reached is that John Smyth could and should have been reported to the police in 2013.

“This could (and probably would) have led to a full investigation, the uncovering of the truth of the serial nature of the abuses in the UK, involving multiple victims and the possibility of a conviction being brought against him.

“In effect, three and a half years was lost, a time within which John Smyth could have been brought to justice and any abuse he was committing in South Africa discovered and stopped.

“This period is characterised by the fact that the UK abuses are revealed to a much wider group, including the Church of England at the highest level.

“The abuses in Zimbabwe are also being discovered. The suffering being experienced by several UK victims continues to have a devastating impact, with a victim attempting to take his life on Christmas Day 2013.”

It was in 2013 that a victim contacted the Bishop of Ely’s office, and his safeguarding officer later informed Bishop Conway and agreement is reached to find support for the victim and to contact the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Cape Town.

Det Sgt Lisa Pearson of Cambridgeshire police is also contacted “regarding disclosures made about John Smyth abuse”.

On August 1 Bishop Conway begins emailing senior church officials in South Africa detailing John Smyth’s links to boys camps, “a serious historic safeguarding situation” “police involvement” and the “rapidity with which John Smyth leaves UK”.

A lengthy series of emails follows between the Ely diocese, the Archbishop of Canterbury and one email exchange between victim and The Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser, regarding finding a therapist.

In September DS Pearson advises the Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser that the John Smyth case “most likely needs to be referred to Hampshire Police as abuse took place in Winchester.

“Police officer advises she will talk to senior colleagues before advising the safeguarding adviser further”.

There then follows a string of emails which express various levels of concern, but little action is taken and by May 2014 the Bishop of Ely still awaits a response from church leaders in South Africa.

And in the same month, says the report, “The Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser also confirms she has ‘discussed the matter with Cambridgeshire Police and they confirmed that they can do nothing because Smyth’s actions, though clearly an abuse of trust and position, would be unlikely to reach the threshold for a criminal investigation and because of the out of time rules’”.

The report also reveals that Bishop Conway agreed to fund therapy sessions for victims, describing this as “I offered to fund counselling sessions for one survivor, which that person declined. I continued to offer support to that survivor for the rest of my time as Bishop of Ely”.

Three therapy sessions funded by Ely were offered to a different survivor who lived in a different diocese.

Bishop Conway says that this was “interim support while they made preparations to provide suitable ongoing support for that individual” adding that this “provides evidence of my sense of duty of care for survivors of abuse”.

Under the heading ‘summary of failures during this period’, Makin says: “There was never a formal referral to Cambridgeshire Police, although a police intelligence report was subsequently sent to Hampshire police where the offences were thought to have occurred.

“Although mentioned during conversations between the diocese and Cambridgeshire Police, no referral was made to Hampshire Police. There is a distinct lack of any clarity about police action”.

Makin concludes: “The Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser took insufficient action.

“There was not, at any point, by anyone involved, a full recognition of the seriousness or the extent of the abuse in the UK. This is despite knowledge of a further abuser and to the fact that another victim had attempted to take his own life.

“The Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser knew that at least three victims were involved in the later part of 2013 that there may have been two abuse perpetrators and that there was a continuing concern regarding the potential for abuses continuing in Africa.

“This knowledge should have been more than enough to raise a serious level of concern that this was a very serious abuse case. Indeed, her knowledge was even greater than this, as she had been told by a victim that around a further five or six victims had suffered abuse.”

He says the review adviser has suggested that she was not immediately aware of the seriousness of the abuse, that she understood victims were adults and that the 2006 House of Bishops policy, “Promoting a Safer Church” was not a useful tool for a complex case such as this.

“The letter to the Church authorities in Cape Town was not followed up in any meaningful and effective way,” he says.

“The Archbishop of Canterbury was ill-advised about the actions taken in the Ely diocese. He was told that a referral had been made to the police. This was not correct.

“A referral from Ely diocese to the Church to alert them to the potential for this being a national and not local case was not pursued. This was a serious error.”

Makin says: “This review does not attempt to explore the detailed reasons why the South African authorities did not follow up the letter from Stephen Conway more vigorously.”

The review focuses on what the Church of England did and did not do.

By 2012/13, safeguarding was in theory established as a concept, with a strong legal underpinning and Government guidance, which applied to all organisations and bodies, including the Church.

“We have demonstrated that this was far from the case, with serious abuse and crimes being covered up at the time,” says Makin.

“This complacency continues with comments from the Bishop of Ely and a lack of serious attention from Lambeth Palace and various police forces. This could have influenced the way that things were handled subsequently and for the abuses in the UK to not be investigated.

“Stephen Conway was in a potentially powerful position to explore this further, to reinforce the referral to South Africa, to ensure that a police referral had been made and was being investigated, and to make sure that the full extent of the concerns regarding this disclosure of serious abuse was being fully pursued.”

Makin says Stephen Conway’s involvement was reviewed by a Church Core Group in 2021.

He admits the outcome of their review may lead to some finding “a judgement of systemic failure within the Diocese of Ely through the lens of safeguarding in 2021.

“An opportunity was missed to halt Smyth and bring him to justice within the UK; however, Bishop Stephen was not in possession of the legacy we know of as John Smyth in 2013”.

There was no policy in place at the time to reflect the risk posed internationally.

Bishop Conway’s response “was consistent with safeguarding culture and practise at the time. The National Safeguarding Advisors did not respond and failed to help the diocese navigate the matter further. The core group recommended ‘a proportionate response is for no further action to be taken’.”

Makin says: “Based on the evidence seen by reviewers and interviews conducted with the key people at the time, it appears to be the case that the serious abuse which was known about by both Ely diocese and Lambeth Palace from early 2013 was not properly investigated.

“There is no evidence of any continuing interest and activity from November 2013 onwards, apart from references in the minutes of the diocesan safeguarding management group in Ely diocese, but with no evidence of any actions being taken.”

A total of five police forces were told of the abuse between 2013 and the end of 2016 – Cambridgeshire, via DS Lisa Pearson and two of her more senior colleagues, London Metropolitan, Surrey and Sussex, Thames Valley, and Hampshire.

“Cambridgeshire Police, via DS Lisa Pearson, were notified of the abuse by Yvonne Quirk, the Bishop of Ely’s safeguarding adviser, in 2013; this took place informally as a discussion and was followed up by two more senior officers at an in person meeting with Yvonne Quirk. This was not recorded as a crime,” says Makin.

The report explores an email from Yvonne Quirk of 23 May 2014 which followed a meeting with the Bishop of Ely where “we had agreed there was nothing more we could do unless a new lead came up from others working on the case”.

Yvonne explained her perspective on that time and reflects; “I was angry and exhausted and had indeed lost my grip. I do not offer any excuse for that decision.

“I have explained the background only because I want to assure the victims of John Smythe that I did not, at any stage, see their plight as some sort of ticky-box exercise that I could casually sign off once I had ticked enough boxes,” she told the review inquiry.

“I recognise now that what I should have done was step back, take a proper break from the case, and then return fresh to my part of the fight. But I did not. I fully accept the criticism levelled at me in that regard.

“To the victims of John Smyth, I apologise directly and unreservedly for that. I am so very sorry. You deserved better.”

The independent review by Keith Makin into the Church of England’s handling of allegations of serious abuse by the late John Smyth was published last week.

The full review can be read here.

Keith Makin, who led the independent review, said: “The abuse at the hands of John Smyth was prolific and abhorrent. Words cannot adequately describe the horror of what transpired.

“Many of the victims who took the brave decision to speak to us about what they experienced have carried this abuse silently for more than 40 years.

“Despite the efforts of some individuals to bring the abuse to the attention of authorities, the responses by the Church of England and others were wholly ineffective and amounted to a coverup.

“The Church and its associated organisations must learn from this review and implement robust safeguarding procedures across their organisations that are governed independently.

“This has been a long process but a necessary one to uncover the extent of John Smyth’s despicable behaviour and how the Church reacted to it.

“The review concludes that Smyth is arguably the most prolific serial abuser to be associated with the Church of England.

“We know that no words can undo the damage done to people’s lives both by him and by the failure of individuals in the Church and other institutions to respond well.

“We are also aware that the time the review has taken, which the reviewer addresses, as well as the details now in the public domain have been retraumatising for survivors.

“We highlight the comment in the review from a deceased cleric (David Fletcher) who was aware in the 1980s, along with others, of the extent of the abuse: ‘I thought it would do the work of God immense damage if this were public’.

“We are appalled that any clergy person could believe that covering up abuse was justified in the name of the Gospel, which is about proclaiming Good News to the poor and healing the broken hearted.

“It was wrong for a seemingly privileged group from an elite background to decide that the needs of victims should be set aside, and that Smyth’s abuse should not therefore be brought to light.

“Every member of the Church is responsible for a culture in which victims are heard, responded to well, and put first: there is never a place for covering up abuse.”

“We are aware of criticisms in the report of individuals and organisations and names of clergy were passed to the National Safeguarding Team, NST, from the reviewer.

“The report also highlights Smyth’s abuse in Zimbabwe, where a boy died and many more were abused.

“It is clear that Smyth went abroad in the early 1980s following the discovery of his abuse here and in full knowledge of the church officers named in the report. The reviewer urges the Church to consider commissioning a report into Smyth’s actions both in Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Smyth, a QC, was the former chair of the Iwerne Trust, which, with the Scripture Union, ran holiday camps for boys at English public schools.

His sadistic abuse included beatings in sound proofed shed.

The earlier Ruston Report from 1982 into his activities offered detailed evidence of the abuse, such as this extract quoted by Makin: “It is evident that those informed by the Ruston Report would have been clearly aware of the grim extent of the abuse, and we hypothesise that this knowledge could have been passed on more widely as word spread among these individuals’ networks and contacts”.

The Ruston Report, for example, quoted this: “The scale and severity of the practice was horrific. Five of the 13 I have seen were in it only for a short time.

“Between them they had 12 beatings and about 650 strokes. The other 8 received about 14,000 strokes: 2 of them having some 8,000 strokes over the three years.

“The others were involved for one year of 18 months. 8 spoke of bleeding on most occasions- ‘I could feel the blood splattering on my legs’ – ‘I was bleeding for 3½ weeks’ ‘I fainted sometime after a severe beating’. ‘I have seen bruised and scored buttocks, some two-and-a-half months after the beating’.

“Beatings of 100 strokes for masturbation, 400 for pride, and one of 800 strokes for some undisclosed ‘fall’ are recorded.”

Makin says that several of the victims’ accounts indicate their experience of sexual abuse, particularly describing John Smyth kissing them, draping himself and/or his arms over them, nakedness, and other indicators of sexual abuse.

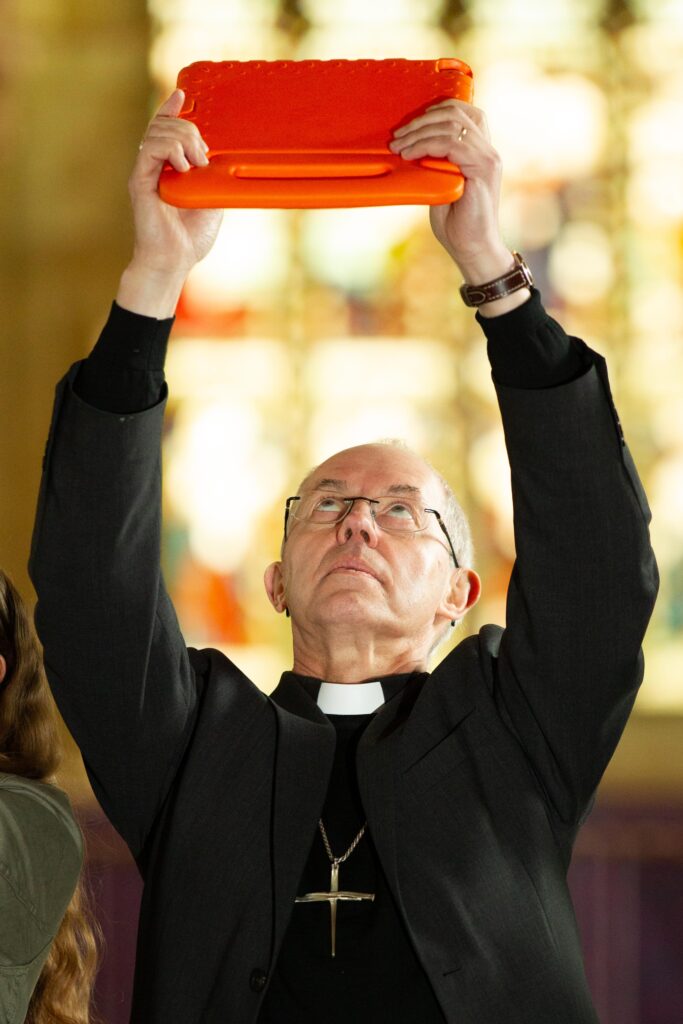

Following the publication of the independent review by Keith Makin the Archbishop of Canterbury said: “The pain experienced by the victims in this case is unimaginable. They have lived with the trauma inflicted by John Smyth’s horrendous abuse for more than 40 years, both here in the UK and in Southern Africa, particularly Zimbabwe.

“I recognise the courage of those victims, including those related to John Smyth, who have come forward and relived their trauma through contributing to this review. I know their willingness to share their painful testimonies will come at great personal cost.

“I am deeply sorry that this abuse happened. I am so sorry that in places where these young men, and boys, should have felt safe and where they should have experienced God’s love for them, they were subjected to physical, sexual, psychological, and spiritual abuse.

“I am sorry that concealment by many people who were fully aware of the abuse over many years meant that John Smyth was able to abuse overseas and died before he ever faced justice. The report rightly condemns that behaviour.

“I had no idea or suspicion of this abuse before 2013.

“Nevertheless, the review is clear that I personally failed to ensure that after disclosure in 2013 the awful tragedy was energetically investigated. Since that time, the way in which the Church of England engages with victims and survivors has changed beyond recognition. Checks and balances introduced seek to ensure that the same could not happen today.

“John Smyth’s abuse manipulated Christian truth to justify his evil acts, whilst exploiting and abusing the power entrusted to him. In the last 11 years much has been learned. This long-delayed report shows another, very important step on the way to a safer church, here and round the world.

“That does not reverse the terrible abuse suffered but I hope that it can be at least of some comfort to victims.

“I can only end by thanking them again for their courage and persistence and again by apologising profoundly, not only for my own failures and omissions but for the wickedness, concealment and abuse by the church more widely, as set out in the report.”